News

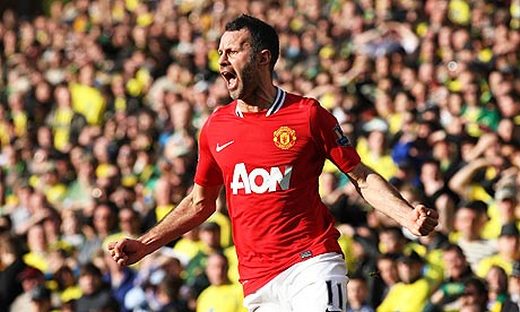

Ryan Giggs, Stanley Matthews and the art of growing old gracefully

Geoffrey Green died in the spring of 1990, at the age of 78, just a few months before Ryan Giggs celebrated his 17th birthday by signing professional forms with Manchester United. So the great football correspondent of the Times never saw a Welsh prodigy whose gifts he would certainly have adored and celebrated in rich prose that vibrated with enthusiasm. But he did have a Ryan Giggs of his own.

"Stanley Matthews in his day conjured a universal affection and admiration," Green wrote in his autobiography. "If a full-back treated him brutally – or tried to – even a home crowd would turn against their own man. Everyone wanted to protect Matthews – not that he needed it. He knew full well how to look after himself. Yet to the man on the terrace he remained one of the nation's crown jewels and had to be preserved."

Who has not felt, to some degree or other, a similar protective feeling about Giggs? In his teenage years, when his curly hair was still as black as Welsh coal, he played with a zest and an innocence that could cut across club loyalties. And even now the spark refuses to die. The injury-time winner with which the 38-year-old marked his 900th match for United on Sunday, a stealthy run followed by a deftly angled touch of the left boot, carried the hallmark of his very best work.

Twenty years after his youthful exuberance and Eric Cantona's sheer foreignness defined the burgeoning box-office appeal of the new Premier League, Giggs is still going strong. He is unlikely to match the achievement of Matthews, who was 50 years and five days old when he made his 758th and last club appearance in February 1965, but he will be on duty again next season, ready to answer the call whenever his manager needs the influence of his accumulated wisdom on team-mates who were not yet born when he first put on a United shirt.

Perhaps, in football terms, 40 is the new 50. Matthews was famous for looking after his fitness but he played the game at "a walk or a slow shuffle", in Green's words, relying on an ability to mesmerise defenders, and was able to trade on his original tricks until the end. In a very different age, one that prioritises speed and strength, Giggs has learnt to adapt his game to the changes in his body, modifying his function within the team and compensating for slowing limbs by putting a premium on intelligent anticipation.

United's other goal against Norwich was scored by Paul Scholes, who is a year younger than Giggs and returned to the side this year after a failed attempt at retirement. On Sunday night Sir Alex Ferguson called them "the two greatest players in the history of the club", which is some statement when the history in question includes such figures as Duncan Edwards, Bobby Charlton and George Best.

Their goals came on the day their contemporary and former colleague Gary Neville wrote a thoughtful column in the Mail on Sunday about the influence on United's players five years ago of a presentation of the techniques used by the MilanLab, the operation at Milan's training centre where the work of chiropractors, kinesiologists and dietitians prolonged the careers of Paolo Maldini, Alessandro Costacurta, Pippo Inzaghi, Clarence Seedorf, Cafu and others – including, for a couple of winters, David Beckham.

The best player in Italy at the moment is Andrea Pirlo, currently 32 and inspiring Juventus's challenge for the championship. Pirlo joined the Turin club after 10 seasons with Milan, and he is making his former employers look silly for their refusal last summer to offer him anything more than a one-season contract. His 2,251 touches in 23 Serie A matches this season put him ahead of every other player in Europe's top five leagues, a remarkable 147 of them coming during the 3-1 win over Catania a couple of weeks ago.

He began his career playing in the hole behind the strikers, as a classic No10. It was while on loan at Brescia that he first dropped deeper, into what is now known as the quarterback role, and when Carlo Ancelotti arrived at Milan, Pirlo offered to do the same thing in order to solve the problem of the club's superfluity of No10s.

"I had my doubts," Ancelotti wrote in his very entertaining memoir. "I was afraid that Pirlo might create problems in terms of timing, because he likes to take the ball and keep it. A safe with a slow combination. I wasn't overly confident in this new approach, but I listened to him and gave it a try. I was astonished. He started playing with beautiful simplicity, and he became an unrivalled player." A few years and two European Cups later Ancelotti wanted to take Pirlo with him to Chelsea, and you have to wonder what might have happened had the coach got his way.

The right kinds of physiology, metabolism and dedication are what it takes to make a player as valuable at 32 as he was at 22. In the case of late-period Giggs and Pirlo, perhaps even more precious: not just to their managers and coaches but to spectators who are being presented with memories that, like those of Matthews cherished by Geoffrey Green, are slow to fade.