News

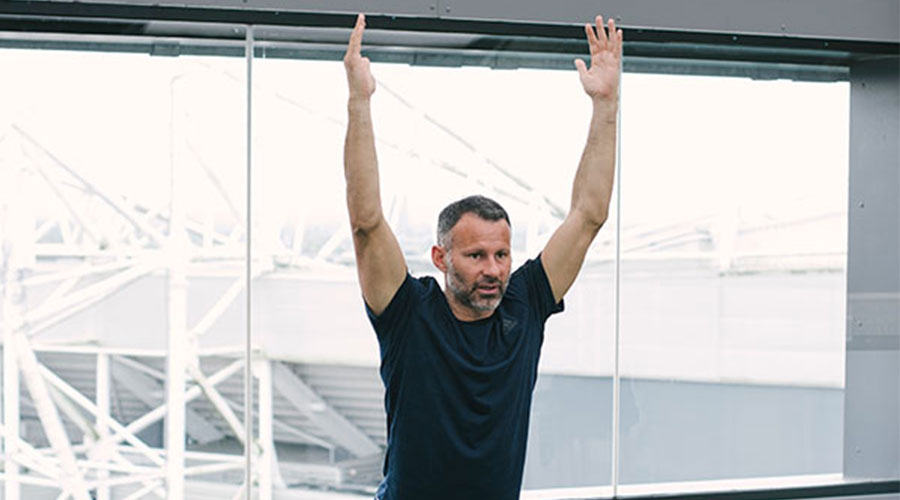

Out of office: Ryan Giggs on his passion for yoga

Ryan Giggs goes through his yoga exercises against a backdrop of the Old Trafford stadium he graced for many years with Manchester United © Christopher Nunn. Read original article at FT Magazine.

Ryan Giggs is deftly poised in the yoga posture of adho mukha svanasana: an inverted V-shape known to lunch-break yoga devotees as the “downward-facing dog”. It seems strange to observe the former Manchester United player so still. From his debut as a swift, slaloming 17-year-old winger in 1991 to his final game as an inventive 40-year-old midfield playmaker in 2014, Giggs energised matches with his intelligent movement and slinking dribbles that, in the poetic words of his manager Sir Alex Ferguson, left opponents reeling with “twisted blood”. However, he credits the longevity of his career to the pursuit of yoga.

“I started yoga after missing a big Champions League game against Bayern Munich [in 2001] through injury,” explains Giggs, 43. We are stretching side by side on the rooftop Astroturf pitch at Hotel Football, a £24m development co-owned by Giggs that overlooks Manchester United’s Old Trafford stadium.

“I went on a dribble in training and pulled up with a hamstring strain. I’d had similar injuries before and I remember sitting in my bedroom thinking, ‘This can’t go on.’ So I tried everything. I changed my car [buying an automatic to reduce leg strain]. I changed my bed for better posture. And I started yoga. It helped me get another 10 years out of my career.”

Kept supple by yoga, he went on to win another 17 pieces of silverware — half of his record haul of 34 major trophies, which includes 13 Premier League titles, four FA Cups and two Champions League trophies. He retired as the most decorated British footballer in history. “Yoga was first about injury prevention, but later it became about recovery. The day after a match, the adrenalin would still be in my body. But the following day, when I got out of bed, everything would hurt, so I would do yoga then. It made me more aware of my body.”

Photographs © Christopher Nunn

Photographs © Christopher Nunn

As Giggs shows me some toe-touching sun salutations, I can’t help glancing at his sockless feet. With them he scored goals that triggered global tidal waves of celebration among his club’s estimated 650 million fans, carrying him through a record 963 appearances. Perhaps his yoga classmates have similar reflections. “I have kept the yoga going in my local village in classes at the school hall on Tuesday and Thursday,” he says. “It’s close to where I grew up [in Salford], so most people know me but some did a double take when I arrived. But I am just part of a group of 25 people. I was never hassled for an autograph, so I could just enjoy being there.”

Having served as a player-coach for David Moyes, Ferguson’s successor at Manchester United, Giggs temporarily took charge when the Glaswegian was sacked in 2014. He then spent two years as assistant manager to Louis van Gaal but when José Mourinho arrived in 2016, Giggs departed. He had hoped for the top job himself but the club opted for the more experienced Portuguese, and Giggs decided to seek “a new chapter and a new challenge” rather than remain as an assistant — a move Mourinho praised as “brave”. Giggs is currently enjoying a grown-up gap year, balancing his business commitments and football management research with time with his children, Libby, 14, and Zach, 10.

“It felt like the right time for a change when José came in. I wanted to do things I hadn’t done before. I went straight into covering the European Championships for ITV and travelled to India to play in a futsal [a type of five-a-side football] tournament. I had never been to India or played futsal, so it was another new challenge. I hadn’t even seen my son play football at the Manchester United Academy; we always had games at the weekend, so I finally did that. The two years under Louis were hard. Not only because his coaching style was different, but because it was mentally taxing, as he was very demanding. But what a brilliant apprenticeship. I feel so much more prepared to go into management myself one day. I feel very relaxed now. I don’t think I realised how much pressure I put myself under during my career.”

Photographs © Christopher Nunn

Photographs © Christopher Nunn

Born in Cardiff in 1973, Giggs can remember kicking a ball against the wall of his grandparents’ house while his mother Lynne chatted inside. He was seven when his father Danny, a professional rugby player, joined a team in Swinton, and the family moved to Manchester. Giggs continued to hone his skills on the streets. “I would just be kicking a ball outside, picking it up whenever a car came by, or practising hitting a spot on the wall. Sometimes it was just kicking a balloon around the house or chipping a ball against the kerb.”

His life-changing moment came, aged 13, when he scored a hat-trick for Salford Boys against Manchester United’s youth team. Alex Ferguson was watching, transfixed, from his office window. He invited Giggs to join the club on his 14th birthday. “I’d seen this big gold Mercedes S-Class at the club, then all of a sudden it was outside my mum’s house, dwarfing it. I walked in and he was having a cup of tea and my mum was offering him a biscuit. What struck me was that he talked about the pathway I would take to the first team. I was 14. It felt a million miles away. But he could see it.”

The former player cherishes two particular memories. “First was the night match against Blackburn [in 1993] when we became champions for the first time in 26 years. I can remember driving my red Ford Escort to the ground and the fans made so much noise I was scared, almost. And then the Nou Camp.” That was the stadium in Barcelona where Manchester United beat Bayern Munich 2-1 in the 1999 Champions League final, lifting the European Cup for the first time in 31 years, with both goals scored in injury time. “It had been so long since the club had won the trophy and the manner of winning it, with a last-minute goal, was just incredible.”

As he shows me the warrior pose (“Just tell me if I am going to break you”), I ask how he maintained such relentless focus. He highlights a mental ability to reset targets. “There was always a reason to win again — whether that was the manager driving me on or pressure from myself to do more, win more, achieve something different.” This attitude was forged in a fiercely competitive working environment. “Sometimes, for me, the training was harder than the games because of our group’s competitiveness and drive.” His former teammate Rio Ferdinand says Giggs even hated losing five-a-side training matches.

The Italian manager Fabio Capello has said Giggs exuded a “special fantasia” but the player insists his creative ingenuity only flourished because it was allied to hard work. “The riches come so easily for young players today that they can fall into the trap of thinking they have already made it. You look at [Manchester United’s 19-year-old striker] Marcus Rashford and you see the cream always comes to the top: he is a good player with the right mentality. But players just underneath that level can become great players with hard work. I saw my own teammates do it. Not everyone understands that.” At pivotal moments in the season Giggs would resist even a sliver of butter on his toast. “I felt I needed that extra edge. I was fine-tuning my body.”

Giggs speaks candidly about the unexpected challenges faced by athletes when retirement brings a sudden end to their closely managed schedules and regular endorphin surges. “Retirement is a big problem. It is not only a case of, ‘What do I do next?’ But when you train every day, it releases something and when you stop getting that, it is hard. You also lose the structure of routine. I lost the energy I had and I needed other projects. People say, ‘You have earned your money.’ But money has nothing to do with it. You have still got to live a life.”

This sentiment has driven Giggs into business with four former teammates, Gary and Phil Neville, Paul Scholes and Nicky Butt. Their Hotel Football development is backed by Singaporean investor Peter Lim and the consortium are planning to expand worldwide, having already launched branches of its sister venue Café Football in London, Manchester and Singapore. “There was a bit of snobbery at first because we are footballers. People think, ‘What do you know about hospitality?’ But there are similarities in sport and business. You do your homework, you work hard and you need a bit of luck.”

With the same consortium, Giggs also owns a share of Salford City FC, who play in English football’s sixth tier. At first, he found it strange dropping into a world of leaking stadium roofs and volunteer tea ladies, but Giggs relishes the grassroots authenticity. “When we first discussed buying a club, I suggested Salford. We all trained there as kids. I am from Salford. Paul Scholes was born there. We all had an affiliation.” He hopes to get the club promoted to the Football League and to build a 25,000-seater stadium. “This is something we can all still be doing in 25 years’ time, so it is a long-term plan.”

Nonetheless, Giggs’ primary ambition is to become a manager. He has completed the Uefa Pro Licence — an 18-month course for trainee managers, which covers everything from tactics to employment law. “I am now doing some work as a technical observer for Uefa. I was at the Leicester against Atlético game recently and I jotted down the teams’ tactics, made a presentation on my laptop and created an in-depth report for Uefa. I am preparing myself to be a manager but I am in no rush.”

Although he was interviewed by Swansea City last year, and has received offers in England and abroad, he is waiting for the right club. “It doesn’t matter in which league or country; it is about finding a club with a good owner and a team who play football the right way.” Ferguson remains on speed dial. “In the past three years I have spoken to him more than I did when I was a player. Actually, he was the one who put me forward for the Uefa job.”

For the first time in a career founded on speed and instinct, Giggs is content to slow down. Perhaps it is another lesson drawn from yoga. “We always finish a session by lying down to calm our breathing,” he says, instructing me to close my eyes. I hear a chuckle. “A lot of the lads in the class fall asleep in this bit. The instructor turns off the lights and away you go.”

I ask Giggs if he ever misses the pulsating thrill of professional football. He pauses and a flicker of emotion is palpable. “It is a feeling you can’t replicate. If I went on a run, the energy the crowd gives you is hard to describe. You couldn’t wait to get the ball again. I always wanted to excite the crowd. Sometimes, running down the wing, you could see the crowd stand up, row by row, along the whole stand. The feeling you got was unbelievable.”

After a few moments he sits up cross-legged and folds his hands together. The stadium that served as his stage for 23 years looms in the window behind him but Giggs is gazing contentedly ahead. He bows his head, smiles, and utters one final salutation: “Namaste.”

Photographs: Christopher Nunn